Fast Away the Old Year Passes: Life’s last words of Hemingway, Hand, and Hearst

A New Year’s Eve Essay

The end of a year has a way of making us think about endings.

We look back over the old year and rack our brains for a clean sentence that makes sense of it. We exert that same effort at the end of a life. In fact, one of our subjects for this episode spent his entire life searching for a single clean sentence. And yet it wasn’t easy to close the books on Ernest Hemingway.

The thirst for a simple sentence to sum up things in a neat way is understandable. But it is also dangerous because lives do not end the way stories end. They do not always hand us a moral. They do not arrange their final moments into a tidy conclusion. Most of us do not get to write our own ending.

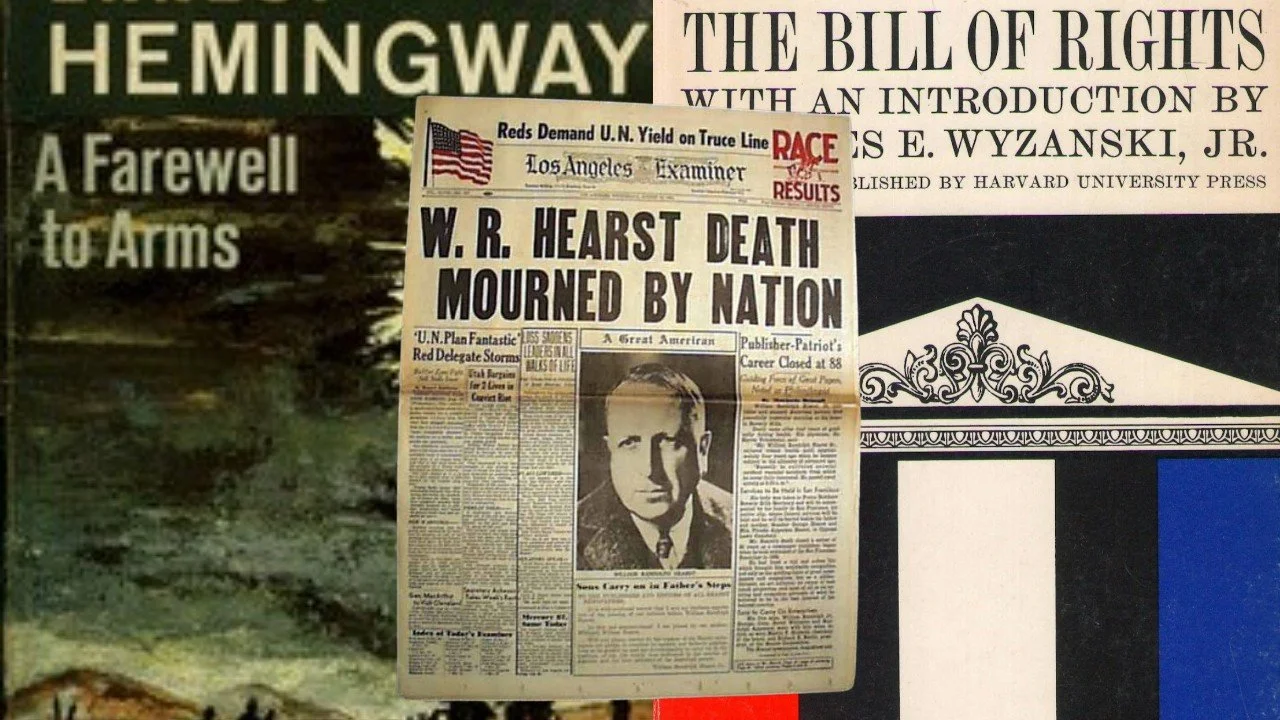

Life magazine is a legend in the American publishing world. Pioneering photojournalism, Life chronicled some of the most turbulent years in human history. It was a weekly visitor to subscribers’ homes until it ceased regular publication in 1972. When my mother died, I discovered she had saved a few magazines. As I sorted through the items that would make up her estate, I noticed the small stack of Life magazines. I picked one up. Because its cover showed a crowd of West Germans at the Berlin Wall. But as I read, I noticed that the selection of articles focused on the recent deaths of two famous Americans. Then I noted a retrospective commemorating the tenth anniversary of another’s passing. I don’t know if the editors planned it, but the juxtaposition of those three articles was poignant. The August 25, 1961, issue presented three American lives to its readers. Each represented a different kind of power. Each left behind “last words” that resist our desire for closure.

Ernest Hemingway was one of the most influential American writers of the twentieth century. He was famous for novels and short stories characterized by spare prose and a flamboyant lifestyle. He was a Nobel laureate whose public toughness masked a deep private struggle. He shot himself to death in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961.

The most respected American judge never to sit on the Supreme Court, Learned Hand shaped modern federal jurisprudence. He championed civil liberties but was wary of judicial overreach. He spent his life defending restraint, humility, and democratic limits.

William Randolph Hearst was the most powerful newspaper publisher in American history. He came to prominence in the days of “yellow journalism.” His newspapers were a force capable of shaping national politics and public opinion. Having forever changed the power of the media to shape public policy, he died after a long physical decline.

At first glance, the contrast among them seems straightforward. The novelist, the judge, and the publisher; creativity, judgment, and influence; art, law, and power. But what makes their juxtaposition so revealing is that their deaths had similar features. None of their final words is what we would expect. What follows is not an attempt to explain these three endings, but to sit with them as Life magazine did. I begin with a letter written in surprising tenderness. Next, I will consider a life ended in humility, and conclude with a final confession of limits.

Hemingway’s “last words,” as Life revealed them, came less than two months after his suicide. They were not a statement to the world or a summation of a literary career. They were a handwritten letter to a nine-year-old boy. Frederic Gordon “Fritz” Saviers was the son of Hemingway’s physician. Young Fritz was in the hospital with a congenital heart condition.

The letter is ordinary. Hemingway wrote about the weather in Minnesota and about his surprise at the beauty of the Upper Mississippi. He continued about hunting pheasants and ducks in the fall. Ernest hoped that they would both be back in Idaho soon to joke about hospital experiences. He signed it as Fritz knew him: “Mister Papa.”

There is no farewell here. No self-interpretation. No hint that “Papa” meant these words to be final. The letter assumed a future.

We now know that assumption is a tragic mistake, yet it is what makes the letter so human. Hemingway did not write toward an ending. He wrote toward a living relationship.

The more we learn about the rest of the story, the deeper it goes. Fritz Saviers himself would die young, at fifteen, in 1967. Yet his life was not one of withdrawal from the limelight. He was a champion schoolboy skier, vigorous and competitive to the end. Today, at the foot of Hemingway’s grave in Ketchum, facing it, lies Fritz’s own grave.

That physical closeness does not complete a story. It refuses to.

Hemingway’s last words remind us how life continues in a relationship even as history prepares to close the book. But Learned Hand’s final season asks a different question. How does a judge’s life, one devoted to judgment, end when final judgment comes?

The Life article on Learned Hand offers no dramatic last utterance. Instead, it gives us a posture.

Hand was old, weak in body, trembling, and the voice quavering. Yet his mind remained alert and serious. He reflected on tyranny, ambition, and human frailty. As was his wont, he resisted straightforward explanations and moral slogans. He distrusted what he called “pretty phrases.” He worried about rationalization. He refused certainty.

Hand did not turn his imminent death into a litany of regrets. He did not claim wisdom in retrospect. He did not sanctify his career. He sprinkled his final words across remembered conversations. His words were consistent with the discipline that marked his life. He prized humility above power, demonstrating restraint in the face of moral temptation.

Where Hemingway’s last words preserved tenderness, Hand’s preserved doubt, and his ending teaches us the discipline of restraint. Hearst’s final years confront us with the harsh truth of what happens when power outlives the body that once commanded it.

William Randolph Hearst lived as a man who sought to shape the reality he chose to report. His newspapers labored to form public opinion rather than record it. For decades, he wielded influence on a national scale.

Life magazine’s retrospective recounted his early years of building a publishing empire. Yet the portrait of Hearst’s final years is a study in diminishing control.

Frail and isolated, he still tried to run his empire. He issued instructions at odd hours about ideological crusades. He worried over foreign affairs and editorial minutiae. But the machinery he had built no longer obeyed him as it once had. Editors pressed harder than he wished. The family and the executives are prepared for succession. Authority slipped, even as the habit of command remained.

Then came the moment that functions as Hearst’s most revealing “last word.” Hearst summoned an editor in anger about a story he believed his staff had ignored. The editor presented Hearst with the published article, written exactly as ordered. The old publisher stared at it, then spoke in a failing voice:

“Mr. Woolard, forgive me. I’m sorry. You know I’m an old man, sick, and I don’t notice things as well as I used to.”

It is the unexpected: an apology.

Hearst died shortly thereafter. His mistress of thirty-five years, Marion Davies, slept through his passing. Doctors sedated her amid family tension. Hearst’s funeral was grand and theatrical, befitting a titan of media and politics. Yet former actress Marion resisted the spectacle, saying, “There’s no need for dramatics.” Hearst died as all men do.

Taken together, these three lives form a revealing New Year meditation. Hemingway, the maker of stories, leaves words that do not foreshadow an ending to his story. Hand, the maker of judgments, leaves life refusing to pronounce judgment. Hearst, the maker of headlines, leaves an apology that admits to diminished power.

None of these great men mastered the meaning of his own death. Could that be the lesson worth carrying into a new year?

Celebrity tempts us to reduce lives to symbols and endings to verdicts. But these three stories resist that impulse. They remind us that we live life forward, not backward. Endings interrupt more than they explain. “Last words” are often not conclusions at all, but fragments of life still in motion.

Hemingway signs, Papa. Hand doubts. Hearst asks forgiveness. Life is not a thing we master. We live it.

I confess to enjoying reading this issue of Life magazine, but these three “last words” left me sad. It is because, while their lives were still in motion, these men finally came to view them as past. You are about to hear what you could construe to be my last words for 2025. I have not mastered life; I don’t expect to; and I am thankful for a second chance, symbolized by the end of an old year and the beginning of a new. I have no idea whether I will make it to the new year. Still, even at seventy, I know real life is only beginning.

As the Christmas carol says, “Fast away the old year passes.” But the next verse says, “Hail the New, ye lads and lasses!”

I say farewell to the old year with part of an old Irish blessing:

Always remember to forget

The troubles that passed away.

But never forget to remember

The blessings that come each day.

And those are you, “ye lads and lasses!” Happy New Year!

Luther and Calvin: Two Reformation Voices on Christmas

Many bloggers focus on the differences between the leading reformers, Martin Luther and John Calvin. A popular topic of debate is their views on Christmas. This is especially true during Advent. While disagreements can be interesting, I have decided to take a different approach. I want to highlight their common ground and complementary contributions to Christmas. To accomplish this, I read their sermons on Luke 2:1-14 side-by-side and compared and contrasted them. This perspective fosters goodwill during this blessed season. However, the popular notion of goodwill toward men is hardly a Reformed understanding. So I offer the following meditation as a follow-up or bonus to the episode on Luther’s Christmas I posted a few days ago.

When Martin Luther and John Calvin approached the story of Christmas, they considered the same stable and the same Child in the manger. But what they emphasized reveals two different Reformation sensibilities. They agree on core convictions, though their spiritual imaginations differ. They are telling the same story with different personalities and objectives. We need all the New Testament gospels, each with its own objectives, yet they tell the same story. Similarly, the Reformers’ diverse perspectives give Christmas its richness.

Both Reformers begin with the same foundational truth:

Christmas is God’s gracious descent. Humanity cannot climb to God; we “scarcely crawl upon the earth,” as Calvin puts it. So God bends low. He takes on our flesh, poverty, helplessness, and imperfect parents who laid him in a crib. This crib was a feeding trough. Neither Luther nor Calvin is sentimental about the village of Bethlehem. It is the first step on the road to Calvary. It is the beginning of Jesus’ humiliating emptying. At Christmas, the celebration of the incarnation of the Second Person of the Trinity, the infinite steps into the finite. In a shocking turn of events, a startled young mother holds the everlasting God in her arms. He disarms the world as the light of God's holiness exposes sinful hearts.

Once they establish that God became man, Luther and Calvin tell the story in different ways.

Luther preaches like a storyteller, almost as if he had wandered into the stable himself. He imagines Mary’s exhaustion, Joseph’s worry, the darkness of the night, and the roughness of the manger. He brings the Nativity down from the stained glass of medieval cathedrals and places it in his own world. He sees the cold stalls of German farms and into the bare rooms of simple houses. Luther’s Christmas is earthy and charged with emotion. He wants us to feel the embarrassment and tenderness of the moment.

For him, the miracle of Christmas is that God took on our vulnerability. Luther dwells on the humanity of Jesus: His crying, His nursing, His helpless and defenseless body. In this humility, Luther finds comfort. Christ did more than become a human; He became ours because the Nativity is personal. “Christ is born for you,” Luther says again and again. Faith makes you a participant in this birth—it is, in a sense, your new birth.

For Luther, good works emerge from this personal union with Christ. One cannot claim to have welcomed Christ in Bethlehem if one ignores Him now in his needy neighbor. The manger is a call to action rather than barn furniture most of us are unfamiliar with, except in a creche.

Calvin approaches the Nativity in a different way. When he enters the stable, he sees the glory of divine majesty alongside the squalor. For Calvin, the angels’ song is a theological marker. It tells us that the Child in the manger never ceased to be the sovereign Son of God. Jesus’ plain poverty reveals Jesus’ divinity without any diminishment. Prophecies and angels work together to magnify the King. And they glorify Him despite unwelcomeness, shepherds, and rags.

Calvin’s imagination is theological and precise. He juxtaposes two grand movements: Christ’s deep humiliation and His undiminished glory. Lowliness and majesty stand side by side in Calvin’s Christmas. They are the twin pillars of hope in the Christmas story.

And while Luther sees neighbor-love emerging from Christmas, Calvin emphasizes the courage of faith. True faith must push past what seems foolish or unimpressive. The shepherds accepted a strange sign: “You will find the Savior of the world lying in a manger.” For Calvin, that sign becomes a pattern for the entire Christian life. God continues to hide His glory under simple forms. We will notice God in gospel preaching, in baptism’s water, and in Communion’s bread and wine. The great of this world overlooked Christ in the stable. So people miss him in humble demonstrations of grace. Yet there, Calvin insists, we find Him.

To exercise faith, we must bow low. It must come without presumption, with a willingness to have shepherds teach us. We must cling to a Christ who does not look glorious to the world but is, in fact, the only source of peace with God. Calvin’s Christmas leads us to worship, obedience, readiness, and endurance. Reconciled, God assures believers of his reign despite poverty, affliction, and persecution.

So how do these two Reformers compare?

Luther treats the Nativity as human. He places us beside Mary and Joseph, and we see humanity honored and redeemed. Calvin gives the Nativity in proportion with humility and glory joined. He fulfills the prophecies and assures his people of deliverance. Luther warms the heart. Calvin steadies it. Luther says, “Christ is born for you, so make His birth your own.” Calvin says, “Christ is your Mediator, so trust Him and do not stumble at His lowliness.”

Together, Luther and Calvin show us that Christmas is both tender and immense:

A Child in the straw, the eternal God in the flesh.

A scene that humbles the proud and lifts the lowly.

A moment where heaven bends to earth and offers hope and deliverance to those who will receive it.

And when you listen to both Luther’s warmth and Calvin’s clarity, you begin to hear the complete harmony of a Reformation Christmas. It is a biblical Christmas about the God-man, and, most of all, about God with us and for us.

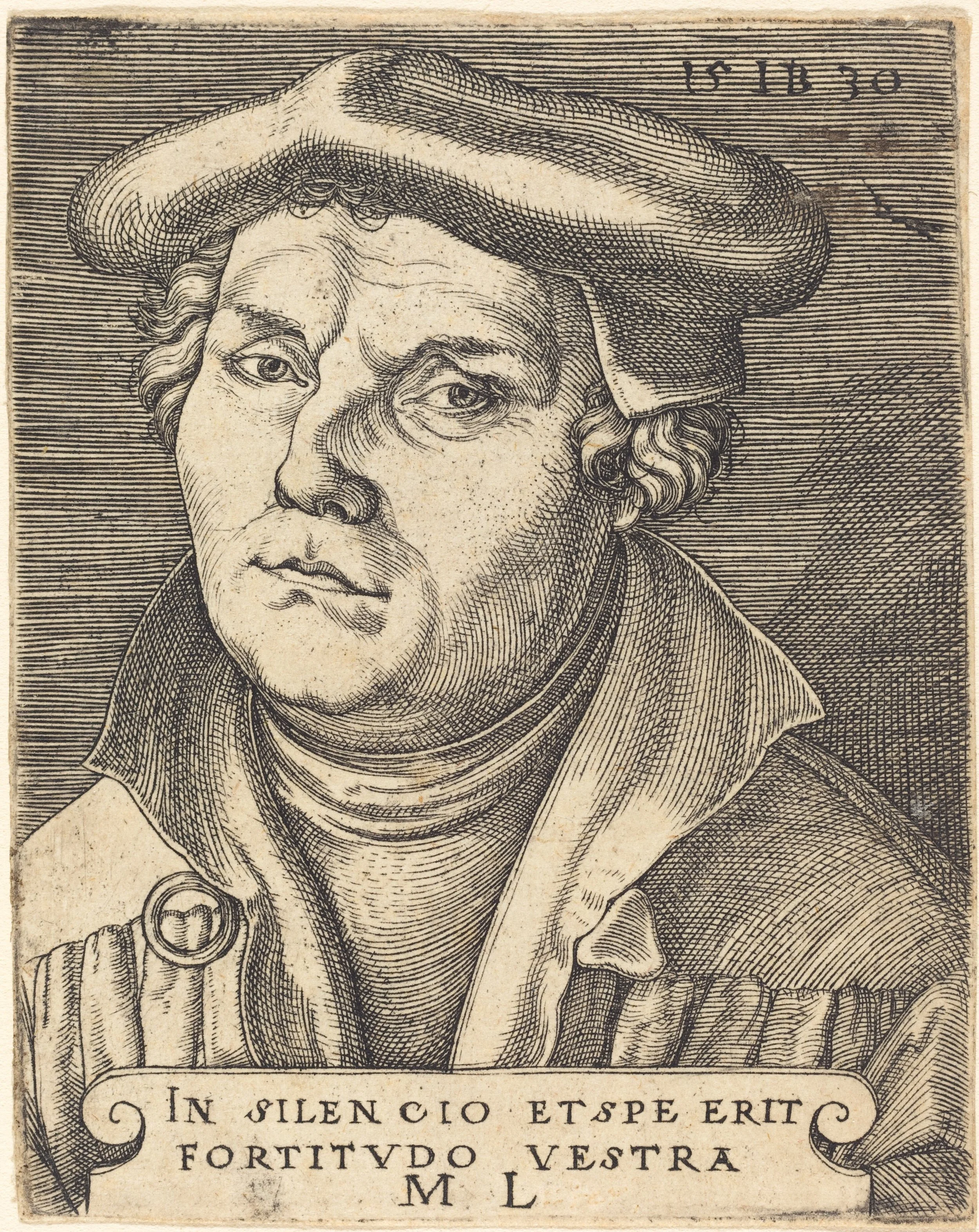

Luther’s Gift: Rediscovering the Hope of Christmas

When I discovered the Reformation in college, it made becoming a historian irresistible. Aside from course textbooks, the first great history book I read was by the late Roland Bainton. It was his biography of Martin Luther, Here I Stand, published in 1950. What a magnificent introduction to historical literature that was! Bainton’s prose was unlike any history book I read up until that time. One reviewer said Bainton had the “ability to balance accuracy with storytelling, making complex theological worlds vivid for general readers while retaining academic integrity.”

Only later did I understand why I breezed through Bainton’s book, not once, but three times. I sensed for the first time that genuine history was a literary project, not a list of facts, causes and effects. Bainton could have been a successful novelist if he had chosen to write fiction.

Each Advent in preparation for Christmas, I read another of Bainton’s published works, Martin Luther’s Christmas. The book includes an introduction by Bainton. It comprises selections from the many sermons Luther preached on the Christmas story. This time, I gathered my zettels, or expanded notes, on Bainton’s insights from the book. I combined them with an actual Christmas sermon by Luther on Luke 2. I was working on a small project for another podcast episode and a blog article that compares Luther’s and John Calvin’s views on Christmas. That is coming up, but I wanted to give Luther his own treatment because he has more of a “heart” for Christmas. (Does Calvin have a head for it?) Calvin is a steady, assuring influence, but Luther is more relatable. I’m not a beer drinker, but if I were, I would want Luther as my drinking buddy! I will say more about these two pillars of the Protestant movement later.

Are you looking for the true meaning of Christmas tonight? Have you bowed your head in despair because its promise is adrift in a sea of naturalism, materialism, and hatred? I know a mentor from early modern history who can help us find it. It is the relatable Luther. The same lovable fellow who called his enemies animal and excrement names. I mean no sarcasm here. My virtual drinking buddy loved Christmas and shared his heart to help us grasp why.

I am saying, if you want to understand Martin Luther’s heart, don’t begin with his polemics; begin with his Christmas. Few passages in the Bible brought Luther nearer to tears than the Nativity story. In fact, when he preached on Luke 2:1-14, you can almost hear him stepping into the stable and gasping at what he sees.

For Luther, Christmas is an invasion, a divine descent so deep and so tender that no words can express it. The eternal God enters the world not in a shimmering palace but in the straw of a borrowed stall.¹

Luther begins by shaking us awake: Christ became our human as bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh. “For you,” Luther says again and again. “For you He is born.”

But Luther loves every detail of the story. He imagines Mary: a poor, unknown girl from Nazareth, trudging southward in winter. She might be riding a donkey. The text does not specify. But she was walking, exhausted and unnoticed.²

He imagines Joseph with no carpenter’s bench nearby, no family home to open, only an innkeeper’s shrug. He imagines their arrival in Bethlehem. The charming “little town” of song. Its out-of-town guests never think to give up a room to a woman in labor.³ Luther says the world is too busy to recognize its Savior.

And then there is the birth. No attendants. No warming fire. No midwife to help. Here is a young mother kneeling on the cold floor of a stable. She bends in the dark, wrapping her infant in whatever cloth she could spare.⁴

The Creator of the universe, the One who shaped Adam from the dust, now lies in a manger where animals feed. “Do you see,” Luther asks, “how God turns the world upside down?” He makes the high low; he lifts the low high. He exposes human wisdom as foolishness, human pride as blindness.

Bethlehem slept through the greatest moment in its history. It expected God in palaces rather than in poverty.⁵Yet Luther is no mere sentimentalist. He sees in the manger the first public declaration of Christ’s mission. Christ submitted to Caesar’s census even while in His mother’s womb. He shows that he has come not to overthrow human authority but to enter into human obedience. He endures poverty. It foreshadows Jesus’ lifelong humiliation that will culminate at the cross.⁶

But for Luther, the deepest miracle of Christmas is not that Christ humbled Himself. It is that He took up our shame to give us His glory. In a remarkable passage, Luther tells his hearers to imagine themselves in Mary’s place. “Make this birth your own,” he says. “Take the Child as if He were born from your own flesh.” For if Christ has taken your humanity, then His innocence becomes your innocence. His pure birth cleanses your impure one.⁷ Luther is particularly moved by the shepherds. They are living proof that the gospel belongs first to the humble and the low. They had no learning, no reputation, no theological sophistication. They heeded the angel’s instructions and went.⁸

And when they arrived, what did they find? Not what any reasonable person would expect. A Savior wrapped in rags instead of silk. The King of kings lying in straw and not eider-down pillows. The sign of God’s redemption, Luther says, is always humble, hidden, wrapped in the ordinary.

And here is one of Luther’s boldest insights: Do you claim you would have welcomed Christ that night in Bethlehem? Then you can show it now by welcoming Him in the person of your neighbor. The manger was a test of the world’s compassion, and the world failed. So every needy person we meet becomes, in Luther’s imagination, another Bethlehem. The presence of a stranger is another chance to receive Christ where we do not expect Him.⁹

Finally, Luther returns to the angels’ song. They say, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace.” He hears in that song the whole Gospel in miniature.

Glory to God, because salvation is His work alone.

Peace on earth, because Christ reconciles sinners to God the Father.

Goodwill toward those He has chosen, because God comes not in wrath but in mercy.¹⁰

For Luther, Christmas is a transformation. The Child in the manger is the God who claims us, cleanses us, and calls us into a life of humble love. The Nativity is not the beginning of Christ’s story; it is the beginning of ours.

Luther’s words were influential. He was the channel through whom Scripture, in the common tongue, changed the course of history. Luther gave Christmas back to people without decorations, song, or liquid cheer. Luther invited us to stand with the shepherds, bend low beside the manger, and consider. Mindful of a shattering truth rather than a quaint scene or a seasonal decoration. The Maker of all things has made Himself small, that He might make us sons and daughters of God.¹¹

Bainton, Roland H. Martin Luther’s Christmas Book. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1948.

Luther, Martin. “Sermons of Martin Luther, vol. 1.” John Nicholas Lenker, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House (1983).

Footnotes

¹ Roland H. Bainton, Martin Luther’s Christmas Book (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1948), introduction and commentary on Luther’s stripping away of medieval Nativity embellishment.

² Bainton, Martin Luther’s Christmas Book, on Luther’s humanizing portrayal of Mary’s poverty and journey.

³ Ibid., Bainton’s note on Luther’s tendency to weave the Nativity into the familiar social world of German domestic life.

⁴ Ibid., discussion of Luther’s focus on the stark and earthy realism of the birth.

⁵ Ibid., on Luther’s theology of the divine hiddenness and the world’s blindness to grace.

⁶ Ibid., on Luther’s linkage of Bethlehem and Calvary—humiliation as a single movement.

⁷ Ibid., summary of Luther’s teaching that Christ’s “pure birth” heals humanity’s “impure birth.”

⁸ Ibid., on the shepherds as paradigms of humble faith.

⁹ Ibid., Bainton’s note on Luther’s ethical turn: modern hearers would have failed Bethlehem’s test.

¹⁰ Ibid., on Luther’s exegesis of the angels’ hymn as a tightly compressed gospel.

¹¹ Ibid., concluding reflections on Luther’s emotionally rich and doctrinally grounded Christmas preaching.

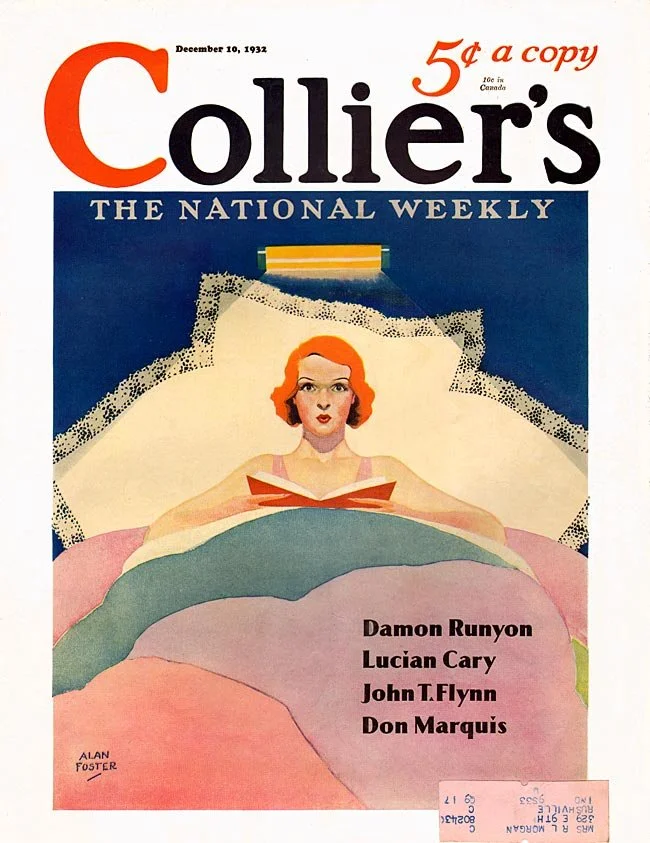

Unexpected Grace: Christmas in Damon Runyon’s Old New York

Some Christmas stories come to us wrapped in ribbon and sentiment, like A Christmas Carol. Other Christmas tales arrive by back alleys, worn stairwells, and smoky rooms. “Dancing Dan’s Christmas,” a tale spun by Damon Runyon, appertains to the latter category. But don’t let its Broadway grit and Prohibition-era slang fool you. There is an old luminosity at its core: the surprising ways grace can find us in unlikely places.

Runyon (1880–1946) was one of America’s most distinctive storytellers. He was a journalist-turned-humorist whose tales rose out of the sidewalks, speakeasies, and racetracks of old New York. Born in Manhattan, Kansas, in 1880, he seasoned as a reporter in the rough-and-ready West. Runyon’s art flourished in that other Manhattan, New York City. From the Little Apple to the Big Apple, where he became a chronicler of Broadway’s colorful characters. Gamblers, bootleggers, chorus girls, and lovable rogues became his subjects. His stories read as if he “overheard them in a booth at Lindy’s delicatessen between bites of cheesecake.” His dialogues were “Runyonese”; full of slang, loads of nicknames, understatement, and street smarts. I have always thought of Sheldon Leonard’s onscreen performances as quintessential Runyonese. Runyon gifted us a lost world that was comic, but all too human.

Runyon’s narrative voice is unmistakable, and his characters have unforgettable names—Dancing Dan, Harry the Horse, Nicely-Nicely Johnson. They are the loveable irregulars we met in Guys and Dolls. The deliberate mismatch between high style and low company makes for linguistic vaudeville. He erects a stage upon which humanity’s follies play out with warmth rather than judgment. Runyon never specialized in Christmas stories, but his work includes several. All reveal a surprising tenderness beneath the hardboiled surface. At Christmas, the Broadway underworld displays capacity for grace, generosity, and unexpected redemption. His Christmas tales remind us that the light gets in, even in the most unlikely neighborhoods.

Collier’s published my favorite Christmas tale of his in 1932. Runyon sets “Dancing Dan’s Christmas” in Good Time Charley’s little speakeasy on West 47th Street. It’s Christmas Eve. Our narrator is one of Runyon’s amiable Broadway philosophers. He sits nursing hot Tom and Jerry’s, a popular egg-based rum-and-brandy holiday cocktail. In walks Dancing Dan, a fellow as light on his feet as he is on responsibility. Under his arm is a cumbersome bundle. Dan is one of those men who seem to float through life, smiling. He dresses to the nines and loves to go dancing. He is always bragging about his latest dancing partner and new questionable enterprises. But he’s also the sort of soul who seems to carry his own weather of cheer with him.

Soon, the holiday spirit is rolling. A street-corner Santa named Ooky is the perfect complement to Dan’s magnetism. The ersatz Claus collapses in the warmth of Charley’s speakeasy. Ooky’s snores are loud enough to rattle the glasses on the bar. This bar is no Currier and Ives Christmas scene—but in Runyon’s world, even the rum-soaked Santa has his place.

When Dancing Dan tries on Ooky’s Santa costume, the evening takes an unexpected turn. Cackles and an atmosphere of inebriation fill the speakeasy. In the midst of this unlikely scene, Dan elevates the conversation with a tender thought. He wants to bring Christmas to Gammer O’Neill, grandmother of the young woman he has been courting. He waxes sentimental over his true love Muriel’s grandma. She is on her deathbed at ninety, but insists upon hanging a patched Christmas stocking. It is Gammer’s last hope that Santa will fill it with goodies. It is the sort of ritual that belongs to childhood—and to those who remember childhood better than we do. Dan enlists Charley and the narrator for a mission of mercy.

So off they go—three men stumbling through the December streets. Dan leads as the disreputable Santa. Charley is eager for adventure, and the narrator is trying to keep his dignity and his balance. They climb five flights of rickety stairs to a tenement flat, where Gammer sleeps with a faint smile on her face. Her world is small, but her hope is boundless.

Then comes the scene Runyon delivers with an almost sacramental tenderness. Dan opens the heavy package he carried into the speakeasy. Inside is a glittering cascade of diamonds—bracelets, rings, necklaces. —the spoils of a major robbery that made headlines that afternoon. Dan assumes a trait of Old St Nick and goes “quick to his work.” Dan fills Gammer’s stocking with the jewelry until the old fabric strains at its seams. The diamonds spill out like a sudden shower of stars.

This extravagance is enough to warm the heart, but Runyon’s Christmas miracle is yet to unfold.

Gammer O’Neill awakens on Christmas morning to a wonder she has waited for all her life. The joy sustains her a few days longer to savor the kindness of a Santa Claus who would visit a fifth-floor walk-up. She dies happy, no longer disillusioned. Granddaughter Muriel returns the jewels to their rightful owner. The police assume the thief had a pang of conscience and abandoned the loot. There is no investigation, but Muriel receives a reward. All seems right with the world, though the holiday has foiled justice.

But the grace runs deeper still. A year later, we learn that Dan’s Santa disguise spared him from a gangland ambush ordered by a jealous rival. Because Dan entered and left Charley’s speakeasy in costume, the hitmen never realized the man they were hunting was already in their line of sight. The red suit and white whiskers—not the diamonds—saved his life.

It is a biblical twist: the man who gives a gift becomes, in turn, the recipient of a grace he did not expect. We are so sure we know the goodness of God when we see it, but there is always more than meets the eye.

Saints do not populate Runyon’s world. Its characters drink too much and talk in deafening tones. They live by a code that would make polite society raise an eyebrow or two. And yet—this is the quiet marvel—Runyon never writes them as villains. He writes them as human beings. Flawed, yes. Compromised, for a fact. But capable of kindness that surprises even themselves.

Dancing Dan’s act is not virtuous in the moralistic sense. It is all-too-human spontaneous tenderness. He sees an old woman’s longing and responds with extravagant generosity. Even the stolen jewels become, somehow enough, instruments of blessing.

It is a reminder that grace does not always appear in the forms we expect. Sometimes it arrives in a speakeasy. Sometimes it climbs five flights of stairs in borrowed boots. And sometimes, as it did for Dancing Dan, it hides a fugitive under the sheltering hood of a Santa Claus suit.

In the Mossbunker, we often talk about cultivating historical consciousness. In part, it is the art of noticing the human pulse inside the past. Runyon’s story gives us a practice ground for that very habit. He invites us to look beyond stereotypes to glimpse the extraordinary imago dei. In the harsh precincts of our world, Gammer O’Neills wait in hope, and Dancing Dans bring surprising mercy.

And so, in this Prohibition-tinted Christmas tale, we find something enduring. Runyon reminds us that the light shines in the unlikeliest corners. And the darkness—whether in South Bronx or Yemen or your own neighborhood—has not overcome it.

Merry Christmas from me, marveling at grace in the Mossbunker.

Want to listen to this post? Go to https://culfinatan.podbean.com/

Here are the sources consulted for the information about Damon Runyon:

Beer, Janet. “The Nicknames in Runyon’s Fiction.” Journal of American Studies 24, no. 2 (1990): 243–253.

Clark, Tom. Damon Runyon: A Life. New York: Paragon House, 1990.

Effrat, Louis. “Damon Runyon’s Language.” New York Times, December 12, 1946.

Hamill, Pete. Why Sinatra Matters. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998.

Joshi, S. T., ed. American Christmas Stories. New York: Penguin Classics, 2018.

Schwarz, Daniel. “Runyon’s Broadway and Its Language.” American Literary Realism 13, no. 3 (1980): 307–312.

Shore, Elliott. Talkin’ Broadway: Damon Runyon and His New York. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

Tully, Jim. “Runyon’s Narrative Technique.” The Bookman, 1932.

Curiosity and attunement

This is the first of three articles about Seven Habits of Historically Conscious People—the basis of a forthcoming book of the same working title.

Do you ever feel lost, like the world makes no sense? The truth is, without historical thinking, it really doesn’t. Oh no, you think, you’re talking about history? Boring! If you think history is boring, it’s probably because no one told you how much it’s messing with your life right now. I’m here to tell you. But fret not. I have seven healthy habits to develop your historical consciousness. In this article, I offer the first two of the seven habits: curiosity and attunement — simple habits you can implement in your own life.

I often discuss historical consciousness because it is the greatest gift that studying history can offer. I refer to it as a learned superpower or the secret sauce of engaging with history. One of my mentors-in-print, historian John Lukacs, wrote a compelling and original book — something I also find loads of fun — published in the late 1960s called Historical Consciousness and the Remembered Past.

Historical consciousness refers to living with a constant awareness of how the past influences the present. To be historically conscious is to live humbly, gratefully, and responsibly in time—remembering the past, reflecting on the present, and preparing for the future. Lukacs said that we might define history not as the remembered past, nor as today, nor as this minute, but that it hasn’t always been that way; it became the remembered past when people began to realize that the past affects us in profound ways. That means there was a time when human beings behaved without consciously recognizing that they were shaped by what had happened before. By “remembered past,” he means the things that happened in the past that we are presently aware of.

Modern people like you and me will have one of two reactions to what I just said. The first response is from people who, in a sense, are still in the old way of doing things: ignorant of the past that shapes their daily lives. They live for the present moment and perhaps give some thought to the future. This first group, which is a diminishing majority, thinks that talk about developing a historical consciousness is, at worst, gobbledegook and, at most, a waste of time. Who cares about the past? It’s old news. What have you done for me lately? They do not realize that they actually dishonor people of the past, their future selves, and their own contributions to the larger story of history by their contempt for the past. This group is embracing “presentism,” judging the past by present standards. Presentism reminds me of that most arrogant of Mark Twain’s books, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Sound harsh? I don’t mean to, but I will talk about this issue in the next episode of this series and unpack it a bit. And by the way, I have designed this series so you can jump in at any point and won’t feel lost. Each episode stands on its own.

Here is the second response of a growing minority who are at least drawn to the past to learn something more about themselves. I am on a mission to convince you that this is the group you want to be in, and you will find this is the “brand” of all my podcasts, vlogs, and blogs. And I am embarking on this mission at the age of seventy, so I am running out of time. I am being too dramatic and self-important there. The second group basically thinks history matters and wants to learn more about it, conscious of its sometimes unperceived impact on our lives. So if you are in this second group, well, we need to talk. So let’s continue to unpack habits that help us step into this advanced role of historical sensitivity.

By the way, those who diminish the past sometimes like to quote the apostle Paul as an ally because he famously said, “Forgetting what lies behind, I reach forward for the upward call of God.” But they are mistaken because what St. Paul was saying was that he had spent his past life building the legalist’s resume to earn his way to participate in the resurrection. But when St. Paul encountered Christ, he learned that one comes to God and the resurrection from the dead not according to one’s personal righteous deeds, but by God’s grace, which led him to faith in something that happened in history —something that — guess what —would affect him now and forever. Paul, at the time he wrote the letter to the Philippians, believed in a historical event that Jesus is God’s Son, lived a perfect life, died on a Roman cross for him, and became the firstfruits of a resurrection that Paul could take part in. So, Paul had to repent by jettisoning his hard-earned resume to receive the free gift of righteousness, acceptable to the One who raises people from the dead: Jesus. Ironic that implicit in Paul’s exercising faith in what Jesus did in history meant leaving Paul’s historical-agnostic position of his own righteousness. In short, St. Paul’s forgetting what lies behind does not mean the whole past, just the defective theology he held up until his conversion.

We all have some awareness of the past, but it can sometimes feel overwhelming to learn history deeply enough to become happier, healthier, and more confident. Think of historical habits as processes to put in place, allowing yourself time to integrate them. You may already have some of these habits or be able to adopt new ones, which may then lead you to others. These habits include curiosity, filling knowledge gaps, reading widely, embracing the golden rule of storytelling, prioritizing history, and seeking to expand your understanding.

To be curious, we must be present with people, both living and dead, and give them our genuine, careful attention.

Interesting stories occur all around us, but often we fail to notice them. We hear people say intriguing things, but we rarely think twice because we are too focused on our own agendas. I speak from personal experience; I often get so caught up in my own projects or become obsessed with my own problems that I neglect to notice those around me. This neglect applies to history as well. We cultivate curiosity by being present, which means giving our full attention to others.

Years ago, I asked my father to share his memories of his childhood in the 1920s and 1930s. He began talking about the neighborhood grocery store owned by my grandfather. My dad worked at the store after school and on weekends. While describing the store, he mentioned, “There was a gas station across the street, where Charlie pumped gas.” My father laughed and added, “The old men always talked about him while they sat around the stove, wondering where he got his money.” He then continued with his story. I interrupted, asking, “Hold on, Dad. What about Charlie? Was he rich or something?” My father replied, “Oh no, nothing like that.” I probed further, asking, “Well, why did they wonder where his money came from?” I remember my father pausing, lifting his shoulders and eyebrows while pushing out his lower lip—a ritual he performed before answering. “Well,” he said, “I guess it was because Charlie would close down the station for a few minutes at noon every day to come across to the store.”

I was curious: “Why did that make the old men think he was secretly rich? Did he load up on groceries?” Dad made a shushing sound, a sign that he was amused. “No, he just came into the store and bought one thing—a five-cent bottle of Coca-Cola. He’d pull it from the ice chest machine, use the bottle opener, and drink it right there in the store because he didn’t want to leave a deposit on the bottle and go back to the station.” I learned a great deal about Depression-era habits from this, but a pressing question remained. “But why did the old men think he was rich? Did you think he was rich?” His reply was, “Oh, I didn’t think he was rich. I just thought he was wasteful, I suppose.”

I was confused. “But Dad, he left the bottle. How was he wasteful?” He explained, “Things were different then. The old men thought it was strange that anyone —let alone a young guy —would spend a nickel a day on a Coca-Cola. And it wasn’t just the nickel, Liam; it was the fact that he was an addict.”

“What?” I exclaimed. “I thought they stopped using cocaine in Coca-Cola by that time.” Dad shook his head. “Yes, you’re right about that. But we thought it must be an addiction for anyone to do something as silly as drinking a soda every day. Why throw away a quarter or thirty cents a week on sugar water that could rot your teeth?”

In that moment, the past came alive. I was not only with my father, but I felt as if someone had opened a door. I could visualize the old men sitting around the stove, looking through the store’s front windows, watching Charlie cross the street. “Here he comes again!” I imagined the red Coca-Cola ice chest lined with galvanized metal, filled with ice and little green bottles capped with red and white. During the Depression, folks treasured those bottles for special occasions of celebration and refreshment. A bottle of Coke would cost nearly a dollar today, which seems almost insignificant now, but during that time of scarcity, even enjoying a daily soda felt extravagant. This sense of excess was prevalent during the Great Depression, which shaped my father’s life and influenced his habits, attitudes, and actions. He never wasted anything. Leftovers were a staple; he saved boxes, hoarded fuses, and made sure everyone in the family used toilet paper efficiently. When my grandfather passed away, we discovered boxes of Prince Albert pipe tobacco tins that he had saved, along with large balls of rubber bands. Hearing the story of Charlie, the Coca-Cola addict, helped me make sense of my father’s peculiar behaviors. It became clear that spending money was seen as irresponsible and extravagant unless the spender maximized it. One can carry frugality too far, but it isn’t a bad idea.

This interaction was a goldmine of information for me. It deepened my understanding of why my father was the way he was, which also allowed me to understand my own story better. I struck upon this rich vein of insight by exercising curiosity, which required me to be present. Because I was paying attention, I picked up on that seemingly strange remark about a gas station attendant. I gained profound insight not only into my father but also into how history impacted my family.

So, curiosity is an essential habit in developing the superpower of historical consciousness. To develop curiosity, we must be present with people, both living and dead, and give them our genuine, careful attention.

Next, let’s move on to attunement. We’re going to “Mind the Gap,” as they warn on the tube in London. The gap is in our knowledge, and we’re not only going to watch our step, we’re going to develop the habit of closing the gaps in our understanding almost painlessly and effortlessly.

*******

Have you ever been sure about a story, only to find out later you only knew half of it? That feeling—that shock of realizing there was more to the story—is precisely what I mean by learning humility in history.

In London, they remind passengers, ‘Mind the Gap.’ It’s a warning to watch your step before you board the train. History gives us the same warning: mind the gap between what we think we know about the past, and what really happened.” I’ll give you four attitudes to help you approach the past with respect and humility.

In a previous episode, I discussed the importance of curiosity as the first habit in developing historical consciousness. However, I would like to discuss another historic railway to illustrate our need for the second habit, attunement, which emphasizes respect and humility and arises from recognizing the gaps in our knowledge of the past. I discussed the importance of curiosity as the first habit in developing historical consciousness. However, I would like to discuss another historic railway to illustrate our need for the second habit, attunement, which emphasizes respect and humility. I love Christ Tarrant’s television series, “Extreme Railway Journeys.” He really understands how much history has been affected by building, maintaining, and travelling on railways.

In the following exchange about The Bridge on the River Kwai and the real “Death Railway” built by Asian slaves, and Allied POWs under Japanese control during World War II, the interviewer (CT) asks historian Andrew Snow how accurately the film reflects what happened. Eighty thousand forced laborers, including 130 Americans, died in its construction. Snow explains that the movie, based on a novel by the same author who wrote Planet of the Apes, takes significant liberties with fact. While some incidents occurred, the central idea of British prisoners teaching the Japanese how to build a bridge is pure fiction. In reality, Snow notes, the Japanese were already highly skilled engineers who knew exactly how to construct a railway. The discussion then turns to the site itself—CT observes that the flood of tourists in casual hats seems disrespectful, given the suffering that took place there. Snow agrees that many visitors do not appreciate the site’s history, often taking short excursions without understanding its background.

During the program, a clip shows a middle-aged Japanese woman tourist marching playfully to the “Colonel Bogey March” music, played by a solo Thai violinist to entertain tourists at the bridge. This familiar tune was the one that the British Commonwealth soldiers were supposed to have whistled to keep up their morale as their Japanese overlords used them as virtual slaves in the building of the railway line that connected Thailand to Burma (present-day Myanmar).

When asked about Japanese visitors, Snow explains that they typically view the bridge as an impressive engineering achievement, since Japanese schools rarely teach the full wartime story. When they do learn what truly happened, he says, they are usually shocked and apologetic, for “you can’t be responsible for something you were never told.”

Snow was very charitable, as a historian should be, toward people with gaps in their historical knowledge. To his credit, and to those he has revealed the full facts of the story, there is sorrow because knowing the truth forces one to reckon with “these were my people” — the truth. And there should be repentance. How can we be sure this never happens again? That kind of response is what we would call attunement; What I like to call “Mind the Gap,” to play on the wonderful warning from the London Underground.

In developing historical consciousness, we must recognize that we frequently do not know the stories of the past, and even when we think we do, our understanding is often incomplete.

The Second Habit that leads to historical consciousness (remembering the remembered past): “Mind the Gap” = attunement. Allow me to describe what I mean by attunement with the past. It comes from Music, the precise adjustment of instruments to produce the correct pitch, symbolizing harmony.

1. Attunement involves being mindful that we are neither omniscient nor detached when it comes to the past. We are characters within the story, not outside it.

History has affected us, whether we recognize it or not. French philosopher Gabriel Marcel believed it was essential to know our ancestors so we could understand their eating habits, which might explain not only how we should eat but also why we have the preferences we do. More significantly, history shapes how and where we find ourselves in this moment. For instance, why was I born in Kansas when my grandfather came from Ulster? My family used to be farmers, so why are none of them farmers today? My maternal grandparents married and lived their lives in ways that were completely different from their upbringing. Why did that happen? How did my town come into existence?

Because we are insiders in our own histories, we have an inherent bias regarding historical events. We cannot judge history, as that would be a proud pretense—unless we are corrupt judges. Judging can look something like these examples:

- “Medieval people were so ignorant; they believed in demons and thought the world was flat.”

- “We shouldn’t respect the founders; they were just racists and misogynists who allowed slavery and denied rights to women!”

- “Martin Luther favored class warfare and aided the knights in their oppression of the peasantry.”

- “Who cares whether the Holodomor—the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s—was intentional or not? Stalin is long dead, and that was a long time ago.”

We arrogantly stand above history when we view our present time as the most enlightened, advanced, and relevant, without considering the context of historical events. Additionally, when a crisis occurs in our time, we often claim it has no precedent, declaring, “This is the worst!” or romanticizing the 1960s as “the best time to be alive!” This attitude reflects pride.

Instead, we need humility: we live our lives within history, not beyond it. John Lukacs stated, “Humility begins when we see that we are not wiser than our ancestors; we are only later.”

2. Attunement also means recognizing that when we encounter the past, we are engaging with real human beings. We should approach their stories with respect, empathy, and caution.

The past is not meaningless; it is not merely useful for proving a point in our favor. Instead, it is complex, and there has never been a golden age we could or should return to. Simultaneously, one should not use history to justify any future utopian vision.

3. Attunement requires us to be truth-tellers regarding the past. Speaking the truth reflects humility in action.

Since we are not outside history, we must acknowledge our assumptions and admit when evidence is scant. Even when evidence is strong, we should refrain from claiming certainty about what happened if we do not have all the facts. We should also allow evidence to challenge our theories and cherished ideas, even if we tie those notions to our core identity.

The Southern writer Flannery O’Connor famously stated, “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.” The true mark of sincere people of faith is their affirmation that “You shall know the truth, and the truth will make you free.” There is no need to fear the truth, even if acknowledging it requires a change. At the same time, the truth cannot be measured by whether it provokes anger, as Gloria Steinem once thought!

4. Attunement involves cultivating a genuine appreciation for the past.

You might wonder how it’s possible to love the past when much of it seems unlovable. Additionally, it’s easy to romanticize certain parts of history, often referred to as the “Golden Age.”

To love the past means acknowledging that the events and people of that time are worthy of understanding on their own terms.

I once attended a class taught by seminary professor John Walvoord, where students were required to present on various theological topics. One student chose to present on a historical figure who had profoundly disagreed with Walvoord on several critical doctrinal issues. Instead of providing a balanced view, the student attacked Walvoord’s opponent in a mocking tone, perhaps believing Walvoord would appreciate it. However, Walvoord interrupted the presentation, stating, “You need to be more charitable. The man you mention has his own story that deserves our respect. In scholarly debate, as in all aspects of life, kindness is essential because it fosters understanding—a quality we should all strive for.”

We may demonstrate our appreciation for the past by a genuine desire to be fair and to listen attentively. Loving the past does not mean idolizing it; instead, it means recognizing that every story, even if we don’t know all the details, is worthwhile and deserving of remembrance.

When reflecting on the past, we should approach it with humility. We can ask ourselves questions like, “How might people in the past have viewed the world?” and “What lessons can they teach us about our own blind spots?” Consider how you would like future generations to remember you, your loved ones, your community, or your country. Would you want them to apply their current standards to you and your experiences, potentially misunderstanding your life and the context of your time? This idea connects to the Golden Rule: we should treat people from the past as we would want to be treated ourselves.

5. Attunement also means being proactive in filling the gaps in our knowledge of the past.

We should strive to read widely and travel as much as possible. Cultivating curiosity can help with this. We should listen attentively and be present when others share their stories, and we may need to consider multiple perspectives on an issue. Don’t you want to continue growing and learning, regardless of what others might think?

We summarize our guiding principle for developing historical consciousness as “Mind the Gap.” Our understanding of the past, even for historians, is inherently imperfect and incomplete, which should encourage humility and a desire to attune to history.

Attunement involves humility (acknowledging that we are part of history and not above it), respect (valuing the past and its people), honesty (letting evidence shape our conclusions rather than preconceived notions), empathy (seeing past individuals as real human beings), love (remembering the past as an act of care for truth and understanding), and persistence (seizing every opportunity to hear others’ stories, both past and present).

Practicing humility means recognizing that both our understanding of the past and the past itself are fragile and human. It is the historian’s way of expressing, “I am part of this story too—therefore, I need to listen before I speak.” Curiosity is also part of attunement as we must be present with people, both living and dead, and give them our genuine, careful attention.

In the next installment of this mini-series, we will explore the third and fourth habits necessary for developing historical consciousness: reading and practicing respect by recalling the golden rule of historical consciousness.

A Haunted Night at Bodsey House — Where History Lives and Legends Linger

I caught a fleeting glimpse of three figures walking away from me. I couldn’t discern any hands or faces…

This is a work of historical fiction based on real-life occurrences. It contains a collage of typical reports about a real place. I confess that I wrote it for fun. The genre is English Ghost story, and the sitz im leben is a cold autumn or winter night, preferably stormy, with a blazing fire, good coffee, and family and friends gathered around. It is meant to be read aloud. Please don’t take it too seriously, even though some of it actually happened—I swear!

I. The Ghostly Trio in the Farmyard

The leafless tree trunks wept with clear, melted liquid, as if they were stout gray candles, unlit against the leaden Cambridgeshire sky. I hugged my heavy coat tightly around my torso as gust after gust of icy New Year’s east winds howled over the fens, warning me against pushing further. A Kansas boy, I was not intimidated by flatlands and winds, even in January, mainly because I was eager to view a relic of history: war-era bunker installations on the farmland. They stood pristine after half a century, still awaiting a German invasion that never came.

I was on holiday with my family, invited to stay at Bodsey Lodge (or House) in the lowlands northwest of Cambridge, England. The core of the house was a thousand years old. It had once been a hunting lodge of King Cnut the Great—the Viking king of England, Norway, and Denmark—a generation before William the Conqueror triumphed over one of Cnut’s successors, Harald, at Hastings in 1066.

I had looked forward to this part of our European tour because I wanted to explore this historical structure and its grounds. I was eagerly anticipating an adventure, but no one else at the lodge wanted to join me after we unpacked. The warm fire, friendly company, and hearty food and drink were too tempting, even for my usually adventurous children. Only a history professor with an insatiable curiosity would venture out in weather like this. Our host had considered accompanying me to examine the site, but suggested we do it the following morning. I, however, could not wait. He told me to walk north, past the farm outbuildings, where I would find the bunker on a little knoll with an unobstructed view of the fens before me.

I was doing my best to navigate the area when, for a brief moment, I forgot about my mission to curse the blustery wind. To my left, to the west, there was a line of trees that marked the toll road, hiding the lodge grounds from the usually busy two-lane road. The friends we traveled with had been here before and mentioned that the lodge was surprisingly quiet, given the steady traffic motoring north toward the historic bridge a kilometer away. The lodge building itself was a break in the trees, its west walls nearly touching the toll road—what an American would call a zero setback, a dangerous faux pas in either architecture or road construction, or perhaps an intriguing conspiracy involving both. To my right, there were impenetrable empty pens and more outbuildings. The only way was forward.

Suddenly, a cloth that had been blowing free wrapped around my ankles, and I struggled to free myself. When I finally raised my head, I caught a fleeting glimpse of three figures walking away from me. I couldn’t discern any hands or faces, only guessed at their gender because they all wore capes— or were they robes? The adult walked between two children, arms draped around their shoulders. I had just enough time to see that the adult’s robe was a dusty black while the children’s capes appeared to be made of soft animal skins. I imagined their coats lined with some wool, but I saw no evidence of that.

I heard nothing, but in an instant, they rounded a corner of an outbuilding and vanished from sight. Was our host aware that they were on the property? They were not far ahead of me, but I knew my shouts wouldn’t reach them over the roar of the wind. So, I ran after them. As soon as I turned the corner, they had disappeared! Before me stood the knoll and bunker. They either went down the knoll, out of my line of sight, or entered the bunker. I assumed the latter and recklessly ventured inside, though I have no recollection of how I did so.

The interior of the bunker was still, damp, and dark compared to the outdoors, but there was enough light to see. The trio was nowhere to be found. I peered out through the slotted openings of the bunker, scanning the fens. They had vanished completely. Without having completed the study I had intended, I dashed outside, looked in every direction, and returned to the spot where I had first seen them, as if I could somehow recreate the sighting. All my efforts were in vain. A deeper chill settled within me, surpassing even the wind, as I made my way back to the lodge, determined to report my experience to our host.

I began to question my senses. Had I really seen them? Had I done everything I could to locate them after I rounded the corner? Who were they?

II. Cnut the Great and the tragedy on Whittlesea Mere

As I walked, I remembered that this place had once been Cnut’s processionary home. Cnut apparently had no central palace; instead, he moved his court with him throughout his realm, showcasing his power rather than focusing on administrative efficiency. The current house was constructed around an eleventh-century hunting lodge, and to the northwest lay Whittlesea Mere. This shallow ancient lake was once the largest lowland lake in England. It measured three miles long and two miles wide, growing in size due to flooding. This flooding issue troubled the Victorians, who undertook a massive drainage project that led to the lake’s disappearance in 1851. The hunting lodge survived because it was built on what would have been an island during flooding. This situation offered a strategic advantage but also made it a dream location for hunters, as wildlife was attracted to the lake. Although the site was isolated, it was connected to village civilization on the other side of the mere by boat.

The most famous story about Cnut concerns his alleged standing on the seashore, commanding the tides to remain still. We may interpret this story in two ways: either as an act of arrogance or as a display of wisdom. The intention behind this event was to convey an essential lesson about spirituality—only God is sovereign. The second most well-known story of Cnut as an English king involves Whittlesea Mere and this particular lodge.

According to A Catalog of Cambridgeshire Folk Tales by Maureen James, published in 2014, a well-known local story recounts:

Cnut built a hunting lodge at Bodsey, near Ramsey, which he could reach by crossing Whittlesea Mere. It was said that Cnut’s twin sons would travel across the mere on their way to school at Peterborough Abbey.

One day, while the sons and their servants were sailing over Whittlesea Mere, a sudden and turbulent storm arose, surrounding them and leaving them in utter despair for their lives. However, by the mercy of God, some were rescued safely from the furious waves. Conversely, others, according to divine judgment, were allowed to pass from this life.

One day, while the sons and their servants were sailing over Whittlesea Mere, a sudden and turbulent storm arose, surrounding them and leaving them in utter despair for their lives.

After the storm subsided and Cnut realized his sons had drowned, he ordered his soldiers and servants to use their swords to mark out a ditch in the marshes between Ramsey and Whittlesey. Then, he commanded workers to clean up the area. The causeway that the soldiers made with their swords became known as the King’s Ditch or Cnut’s Dyke.

The lasting nature of this story is shown in an event that happened in February 1913, reported in the Cambridge Independent Press. During excavations at a monastic cemetery in Peterborough, two tiny coffins were discovered. At first, many believed this finding confirmed the final resting place of Cnut’s twin sons, as the coffins were dated to the eleventh century. But, the bodies inside were only about 2.5 feet tall, suggesting they were infants or toddlers.

The problem arose from this: by that time, Cnut’s sons would have been between six and ten years old, the typical age for attending the abbey school. In the twentieth century, popular opinion shifted back to a local tradition that the sons were buried beneath the flagstones in the central hall, or ermitage, of Bodsey Lodge, the very house where my family was staying for a few days. I suddenly found myself intrigued by that central hall. I didn’t need to wonder if I would be able to see it, as we would be dining in that room tonight—perhaps over the graves of two princes from pre-Norman England.

My history training usually dismisses undocumented tales, but I had to admit, with a chill running down my spine, that I was curious about the three cloaked figures I had seen in the farmyard. I was determined to keep this apparition to myself and see if a reasonable explanation surfaced. I returned to the lodge, put on my best face, and joined in the warm fellowship. Yet, at the forefront of my mind were those three cloaked figures. I wondered…

III. A Bump in the Fright

The hosts had instructed us to gather in the dining room, the oldest part of the lodge, which remains from Cnut’s main hall. As I entered the room, I noticed it didn’t seem very grand or spacious, but I was surprised to find that the ceiling was higher than I had expected. I went up to our room on the second level, which the British call the first floor. Our bedroom overlooked the toll road on the west side, alarmingly close. I wanted to change into something more appropriate and found my wife, Precious (yes, that is her real name), there. She was fastening an earring and appeared to be preoccupied.

“Where are the kids?” I asked.

“They’re already downstairs,” Precious replied, fastening her earring. “They’re excited about the story our host told them—laughing about dining on the graves of Viking princes.”

“Well, that’s understandable,” I said, smiling faintly. “I have to admit, I love the idea of this place. Imagine—a thousand-year-old building.”

“Hold on there, professor,” she said, her voice flat. “Only that dining room is that old. The rest of the house was added bit by bit over the centuries.”

“Yes, yes, of course,” I said, shifting my weight. “But tell me… what’s wrong? You don’t quite seem yourself.”

She hesitated. “I don’t know. The whole idea of eating dinner over the graves of those little boys creeps me out, even if it was a thousand years ago.” Her eyes flicked toward the door. “And…”

“And what?” I asked. “Is there something you’re not telling me?”

She toyed with the earring for a moment, as though buying time. Then she met my eyes. “Liam, twice, walking between here and the bath, I felt… something.”

“And?” I prompted.

“Oh, it’s silly. I’m probably tired and imagined it. Anyway, we should get to the dining room. The kids have been there for a while.”

I know that tone. Precious was trying to close the subject. But something in her voice made me press. “Not until you finish. What happened in the hall?”

“Nothing. I imagined it. A muscle cramp or something.”

“A muscle cramp?” I said, raising an eyebrow. “You’d better tell me.”

She exhaled, resigned. “All right. When I walked to the bathroom, it felt like someone pushed me against the wall.”

“That doesn’t sound like a cramp.”

“Fine,” she said sharply. “It felt like someone was hurrying down the hall toward me and brushed me aside. It happened again a few minutes ago. The floors are uneven. I must have slipped.”

It was true—the place had no accurate angles, no level floors. Still, I shook my head. “You didn’t slip. And deep down, you know it wasn’t a cramp.”

She stared at me. “Then what?”

“You were pushed.”

“Oh, Liam,” she whispered. “You’re scaring me. There was no one there.”

I mumbled, more to myself than to her, “Yes, there was. Someone’s come to play.”

“What? What did you say?”

“Nothing,” I said quickly. “Forget it. We’d better get to dinner.”

She seemed relieved to let the subject go.

IV. Voices and Comfort in the Central Hall

The dining room was warm with firelight, but our children were unnervingly still. Hope and Jesse sat rigidly in their chairs, their usual mischief replaced with blank stares. I tried to sound cheerful.

“Hey, guys. How long have you been here?”

“Shush, Dad,” Hope hissed.

“Shush?” I echoed. Hope was eleven and spirited, but she had never told me to shush before.

“He’s gone, Hope,” ten-year-old Jesse said quietly.

“Dad scared him away,” Hope snapped. “We want to go find him.”

Precious’s voice cut through. “I don’t want you wandering around this house by yourselves.”

“I’m staying here,” Jesse said quickly. “I don’t want to go with Hope.”

“I can’t go alone!” Hope shot back. “You have to come with me.”

“Hope’s a scaredy-cat,” Jesse teased.

“Am not! Besides, you almost cried,” she retorted.

I raised my voice just enough to stop the squabbling. “Hope, who’s gone?”

“The little boys,” she said. “We heard them crying, but we couldn’t see them.”

“Yeah,” Jesse added, “but the light thing was swinging back and forth. Like a monkey was playing on it.”

“Liam!” Precious snapped, as though this were somehow my doing.

Just then, our hosts and friends entered. I leaned toward the kids. “Keep this to yourselves, all right?”

“Why?” Jesse whispered.

“Just do it,” I hissed back.

Our host appeared—a slight, balding man with a fringe of white hair and a short grey beard. His glasses caught the firelight; his blue eyes sparkled with the look of a man who knows something. He set down a plate of rolls and honey.

“I’ll do as you say, Liam,” he chuckled. “But what do you want me to do?”

I felt my ears burning. Precious later told me they’d turned scarlet.

“Oh, nothing,” I muttered.

“I imagined you might have met one of our ghosts,” he said lightly.

“So you know about them?” I asked before I could stop myself.

He looked amused. “Know about them? I live here. They’re buried under us.” He tapped the flagstones beneath the table. “Two Viking princes. Cnut’s twin sons. They’re not always around, but with children here…” He let the thought dangle.

His wife swept in with more food. He moved easily around the table, watching our faces with quiet amusement. “Oh, come on,” he said finally. “You don’t believe in ghosts, do you?”

“No,” I replied automatically.

“Neither do I,” he said, his voice softening. “But I do believe in the supernatural world. Just like C. S. Lewis did, and as you do.”

“Of course,” I said, matter-of-fact, as if we were discussing the weather.

“I can’t prove what they are,” he continued, “but I believe they’re… playing roles. Their activity’s been increasing lately. But let’s not spoil the evening. We’ve grown used to them over the years. You may, too.” And so we ate.

The food was warm and familiar; the flagstones beneath our feet were not. The princes—or whatever they were—kept their distance but, as our host put it, stayed “underfoot.” We lingered at the table longer than was wise, reluctant to part with the firelight and company. But eventually, we climbed the creaking stairs and retired to our rooms. The house settled around us—or perhaps it didn’t.

V. The Flashing Lights

All four of us encountered the hallway bully that night. My wife and I were unsettled; the children, perversely, found it thrilling, making extra bathroom trips as though it were an amusement ride. The wind grew sharper outside, the house colder. The bedclothes were heavy, almost oppressive. Still, they slept—blissfully unaware of what might walk those halls.

I awoke to a crash. Our door had slammed open, striking the wall with a force that shook me out of half-sleep. Beside me, my wife stirred, mumbling, “No… no, no, no!” Her fear was contagious. For a heartbeat, I expected to see the caped figures looming in the doorway.

Instead, it was Doug and Carrie.

“Don’t you knock?” I snapped, my heart still hammering.

“Take it easy, take it easy!” Doug hissed, hands raised like a man talking down a wild animal. “We’re losing our minds and just got a little excited.”

“Losing your minds?” I said. “I’m guessing it’s not the plumbing.”

He gave a nervous laugh. “The lights in the north bedroom kept turning on after we switched them off. Five, six times. We thought it was a short.”

Carrie picked up where he left off. “I told him to unplug it. He did. And then the unplugged lamp came on.”

“That,” Doug said flatly, “was the limit.”

My wife had gone to check the children and returned shaking her head. “They’re still asleep somehow. I brought extra sleeping masks. Why don’t you try them?”

Doug grimaced. “I doubt sleep’s in the cards.”

“It’s two in the morning,” Carrie coaxed. “Let’s try. We need rest.”

“You know,” I said, leaning back, “your room overlooks what used to be the mere. There’s a storm blowing in. People have reported lights out there for centuries, long before there was electricity. Some say it’s someone still trying to guide the boat back to shore.”

Doug’s jaw slackened. Carrie laughed softly. “See, Doug? They’ve been here long before us, and they’ll be here after we’re gone.”

She herded him back down the corridor with masks in hand. They passed the rest of the night almost without incident. I wish I could say the same for myself.

VI. Confrontation in Cnut’s Ermitage

I opened my eyes at 4:00 a.m. exactly. The kind of hour when night has thinned but refuses to let morning in. One look at the clock, and I knew I had finished sleeping. I sat up. Precious wasn’t there. I pulled on my robe and slippers, checked the bathroom—empty. I wasn’t alarmed yet. I thought she might be in the children’s room. But when I opened their door, I froze. The beds were neat, untouched. The room was empty.

The panic came swiftly. The only other possibility was Doug and Carrie’s room. I made my way down two turns of an older, narrower corridor, the air colder with each step. At the end of the hall, a faint flicker of light shone under their door. The lamps were still going mad. I didn’t bother knocking. I pushed the door open. The light blinked off almost the instant I entered—but not fast enough to hide what I saw: two perfectly made beds. No one inside. The room was as empty as the rest of the house.

There was nothing for it now but to go downstairs and check the hosts’ apartment. The door to their section of the house stood ajar, the darkness behind it unbroken. There was no one there.

I passed through the kitchen, my steps muffled on the uneven floorboards, and stopped before the swinging door that led to the dining hall. For several long seconds, I just stared at it, weighing my nerve. Even if my family wasn’t inside, I felt certain the answer to this mystery lay there. I told myself, they may need me. I have to find out what’s waiting.

That sounded melodramatic, but fear has a way of pulling odd performances out of a man. I felt like a poor understudy thrust into a role he didn’t want.

I pushed the door open against the cold brass plate and stepped into the hallway. If anything, the air here was more frigid than in the rest of the house. But something was off at once: in the massive medieval fireplace, a roaring fire crackled and spat—yet the room remained icy. My breath fogged in the air, and the flames threw long shadows across the flagstones.

My eyes, drawn first to the fire, slowly scanned the rest of the room. Then I saw them.

Or rather—them.

The three caped figures stood in the shadows on the far side of the hall: an adult and two smaller shapes, most likely children. Their faces were turned away from me toward the blank wall. For a moment, I couldn’t move. I was frozen, rooted to the spot like prey that knows it’s already been seen.

When I get nervous, I talk too much. It’s a reflex, a bad one. So I blurted out, “What have you done with my family and friends?”

A high, metallic voice answered, brittle as breaking glass.

“The children need playmates. They will stay with us.”

“And the others?” I demanded.

“We will deal with them as we see fit. You should not have come to the Fens. The king is not pleased. This is his domain.”

I swallowed hard, forcing my voice to steady. “Before I ask the obvious question, can I satisfy a historian’s curiosity?”

“Your time is short,” the voice hissed. “But ask.”

“What kind of eleventh-century ghosts speak modern English? You shouldn’t even know what a historian is. Historical consciousness didn’t exist in your era.”

The temperature rose sharply, the heat biting into my skin. Though the figures’ faces were hidden, I could feel the fury in the room shift toward me like a physical force. This fellow didn’t care for history.

“You have talked too much. The children are bored. And as for your unspoken question—we know you wonder what we will do with you. Step toward the fire.”

“And if I don’t?”

“You already know. You have no choice.”

Before I could move—or refuse—my body lifted from the floor. My toes scraped the stone as an invisible pressure propelled me forward. My arms and legs were locked. Slowly, inevitably, I was drawn toward the flames. The closer I came, the hotter it grew, until my eyes burned as though they might melt before my skin.

Then came a violent surge forward—a jolt of unbearable heat—

—and everything went black.

VII. Denouement

“Liam. Liam. Wake up.”

It was my wife’s voice, warm and familiar. A hand pressed my shoulder. For a moment, relief flooded me. Then came the slap—a hard, ringing slap across my face. That wasn’t heaven.

“Liam, you’re scaring me to death. Wake up.”

I opened my eyes. Precious was nearly sitting on my chest, wild-eyed. Behind her, Hope and Jesse giggled in the doorway, clearly delighted by the spectacle of their mother whacking me awake.

“It’s morning,” she said briskly. “We’re dressed, packed, and ready to leave for London. Doug and Carrie are coming with us. Our hosts thought it best—apparently, the children have attracted a little… interest.”

“Fine with me,” I muttered, still half dazed. “But wait—how did you escape the caped ghouls?”

“What?” they said in chorus.

I realized I’d never told anyone about my earlier encounter in the farmyard.

“Did he say cape gulls?” Carrie asked, sticking her head into the room.

I felt like Dorothy waking up in Kansas after Oz. “I thought they were going to immolate me,” I said weakly. “I challenged their ghostly credentials.”

My wife rolled her eyes. “Liam, that was your dream. It didn’t happen.”

My children laughed again.

But the smell of wood smoke still lingered in my nostrils. And my feet, strangely, still felt cold.

“Well, whaddaya know?” I said, my voice still groggy. “Just like Hollywood. All a dream. The next thing you’ll tell me is that the credits are about to roll. Why, when Doug and Carrie crashed our room—”

“No, Liam.” Precious cut me off. Her tone was firm, and that alone made me sit up a little straighter. “That part was real. They had to change rooms. Even with the sleeping masks, the lights kept going on and off.”

I blinked. “Then… all the other stuff happened too? The voices in the hall, the crying children, the bumps in the night—”

I stopped.

For reasons I can’t explain, I held back the one detail that mattered most: the ghostly trio I had seen in the farmyard. That was mine alone—or it had been.

“Yes,” Precious said quietly. “All of it happened. But I’m not as scared as I was last night. Maybe I should be. Now, can you please get up so we can leave before I change my mind?”