Unexpected Grace: Christmas in Damon Runyon’s Old New York

Some Christmas stories come to us wrapped in ribbon and sentiment, like A Christmas Carol. Other Christmas tales arrive by back alleys, worn stairwells, and smoky rooms. “Dancing Dan’s Christmas,” a tale spun by Damon Runyon, appertains to the latter category. But don’t let its Broadway grit and Prohibition-era slang fool you. There is an old luminosity at its core: the surprising ways grace can find us in unlikely places.

Runyon (1880–1946) was one of America’s most distinctive storytellers. He was a journalist-turned-humorist whose tales rose out of the sidewalks, speakeasies, and racetracks of old New York. Born in Manhattan, Kansas, in 1880, he seasoned as a reporter in the rough-and-ready West. Runyon’s art flourished in that other Manhattan, New York City. From the Little Apple to the Big Apple, where he became a chronicler of Broadway’s colorful characters. Gamblers, bootleggers, chorus girls, and lovable rogues became his subjects. His stories read as if he “overheard them in a booth at Lindy’s delicatessen between bites of cheesecake.” His dialogues were “Runyonese”; full of slang, loads of nicknames, understatement, and street smarts. I have always thought of Sheldon Leonard’s onscreen performances as quintessential Runyonese. Runyon gifted us a lost world that was comic, but all too human.

Runyon’s narrative voice is unmistakable, and his characters have unforgettable names—Dancing Dan, Harry the Horse, Nicely-Nicely Johnson. They are the loveable irregulars we met in Guys and Dolls. The deliberate mismatch between high style and low company makes for linguistic vaudeville. He erects a stage upon which humanity’s follies play out with warmth rather than judgment. Runyon never specialized in Christmas stories, but his work includes several. All reveal a surprising tenderness beneath the hardboiled surface. At Christmas, the Broadway underworld displays capacity for grace, generosity, and unexpected redemption. His Christmas tales remind us that the light gets in, even in the most unlikely neighborhoods.

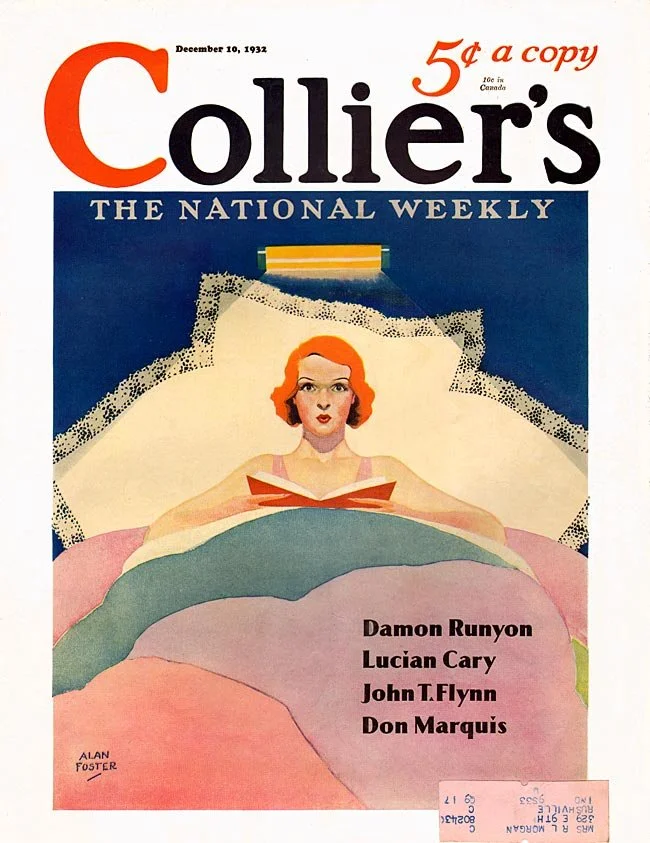

Collier’s published my favorite Christmas tale of his in 1932. Runyon sets “Dancing Dan’s Christmas” in Good Time Charley’s little speakeasy on West 47th Street. It’s Christmas Eve. Our narrator is one of Runyon’s amiable Broadway philosophers. He sits nursing hot Tom and Jerry’s, a popular egg-based rum-and-brandy holiday cocktail. In walks Dancing Dan, a fellow as light on his feet as he is on responsibility. Under his arm is a cumbersome bundle. Dan is one of those men who seem to float through life, smiling. He dresses to the nines and loves to go dancing. He is always bragging about his latest dancing partner and new questionable enterprises. But he’s also the sort of soul who seems to carry his own weather of cheer with him.

Soon, the holiday spirit is rolling. A street-corner Santa named Ooky is the perfect complement to Dan’s magnetism. The ersatz Claus collapses in the warmth of Charley’s speakeasy. Ooky’s snores are loud enough to rattle the glasses on the bar. This bar is no Currier and Ives Christmas scene—but in Runyon’s world, even the rum-soaked Santa has his place.

When Dancing Dan tries on Ooky’s Santa costume, the evening takes an unexpected turn. Cackles and an atmosphere of inebriation fill the speakeasy. In the midst of this unlikely scene, Dan elevates the conversation with a tender thought. He wants to bring Christmas to Gammer O’Neill, grandmother of the young woman he has been courting. He waxes sentimental over his true love Muriel’s grandma. She is on her deathbed at ninety, but insists upon hanging a patched Christmas stocking. It is Gammer’s last hope that Santa will fill it with goodies. It is the sort of ritual that belongs to childhood—and to those who remember childhood better than we do. Dan enlists Charley and the narrator for a mission of mercy.

So off they go—three men stumbling through the December streets. Dan leads as the disreputable Santa. Charley is eager for adventure, and the narrator is trying to keep his dignity and his balance. They climb five flights of rickety stairs to a tenement flat, where Gammer sleeps with a faint smile on her face. Her world is small, but her hope is boundless.

Then comes the scene Runyon delivers with an almost sacramental tenderness. Dan opens the heavy package he carried into the speakeasy. Inside is a glittering cascade of diamonds—bracelets, rings, necklaces. —the spoils of a major robbery that made headlines that afternoon. Dan assumes a trait of Old St Nick and goes “quick to his work.” Dan fills Gammer’s stocking with the jewelry until the old fabric strains at its seams. The diamonds spill out like a sudden shower of stars.

This extravagance is enough to warm the heart, but Runyon’s Christmas miracle is yet to unfold.

Gammer O’Neill awakens on Christmas morning to a wonder she has waited for all her life. The joy sustains her a few days longer to savor the kindness of a Santa Claus who would visit a fifth-floor walk-up. She dies happy, no longer disillusioned. Granddaughter Muriel returns the jewels to their rightful owner. The police assume the thief had a pang of conscience and abandoned the loot. There is no investigation, but Muriel receives a reward. All seems right with the world, though the holiday has foiled justice.

But the grace runs deeper still. A year later, we learn that Dan’s Santa disguise spared him from a gangland ambush ordered by a jealous rival. Because Dan entered and left Charley’s speakeasy in costume, the hitmen never realized the man they were hunting was already in their line of sight. The red suit and white whiskers—not the diamonds—saved his life.

It is a biblical twist: the man who gives a gift becomes, in turn, the recipient of a grace he did not expect. We are so sure we know the goodness of God when we see it, but there is always more than meets the eye.

Saints do not populate Runyon’s world. Its characters drink too much and talk in deafening tones. They live by a code that would make polite society raise an eyebrow or two. And yet—this is the quiet marvel—Runyon never writes them as villains. He writes them as human beings. Flawed, yes. Compromised, for a fact. But capable of kindness that surprises even themselves.

Dancing Dan’s act is not virtuous in the moralistic sense. It is all-too-human spontaneous tenderness. He sees an old woman’s longing and responds with extravagant generosity. Even the stolen jewels become, somehow enough, instruments of blessing.

It is a reminder that grace does not always appear in the forms we expect. Sometimes it arrives in a speakeasy. Sometimes it climbs five flights of stairs in borrowed boots. And sometimes, as it did for Dancing Dan, it hides a fugitive under the sheltering hood of a Santa Claus suit.

In the Mossbunker, we often talk about cultivating historical consciousness. In part, it is the art of noticing the human pulse inside the past. Runyon’s story gives us a practice ground for that very habit. He invites us to look beyond stereotypes to glimpse the extraordinary imago dei. In the harsh precincts of our world, Gammer O’Neills wait in hope, and Dancing Dans bring surprising mercy.

And so, in this Prohibition-tinted Christmas tale, we find something enduring. Runyon reminds us that the light shines in the unlikeliest corners. And the darkness—whether in South Bronx or Yemen or your own neighborhood—has not overcome it.

Merry Christmas from me, marveling at grace in the Mossbunker.

Want to listen to this post? Go to https://culfinatan.podbean.com/

Here are the sources consulted for the information about Damon Runyon:

Beer, Janet. “The Nicknames in Runyon’s Fiction.” Journal of American Studies 24, no. 2 (1990): 243–253.

Clark, Tom. Damon Runyon: A Life. New York: Paragon House, 1990.

Effrat, Louis. “Damon Runyon’s Language.” New York Times, December 12, 1946.

Hamill, Pete. Why Sinatra Matters. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998.

Joshi, S. T., ed. American Christmas Stories. New York: Penguin Classics, 2018.

Schwarz, Daniel. “Runyon’s Broadway and Its Language.” American Literary Realism 13, no. 3 (1980): 307–312.

Shore, Elliott. Talkin’ Broadway: Damon Runyon and His New York. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

Tully, Jim. “Runyon’s Narrative Technique.” The Bookman, 1932.