Luther’s Gift: Rediscovering the Hope of Christmas

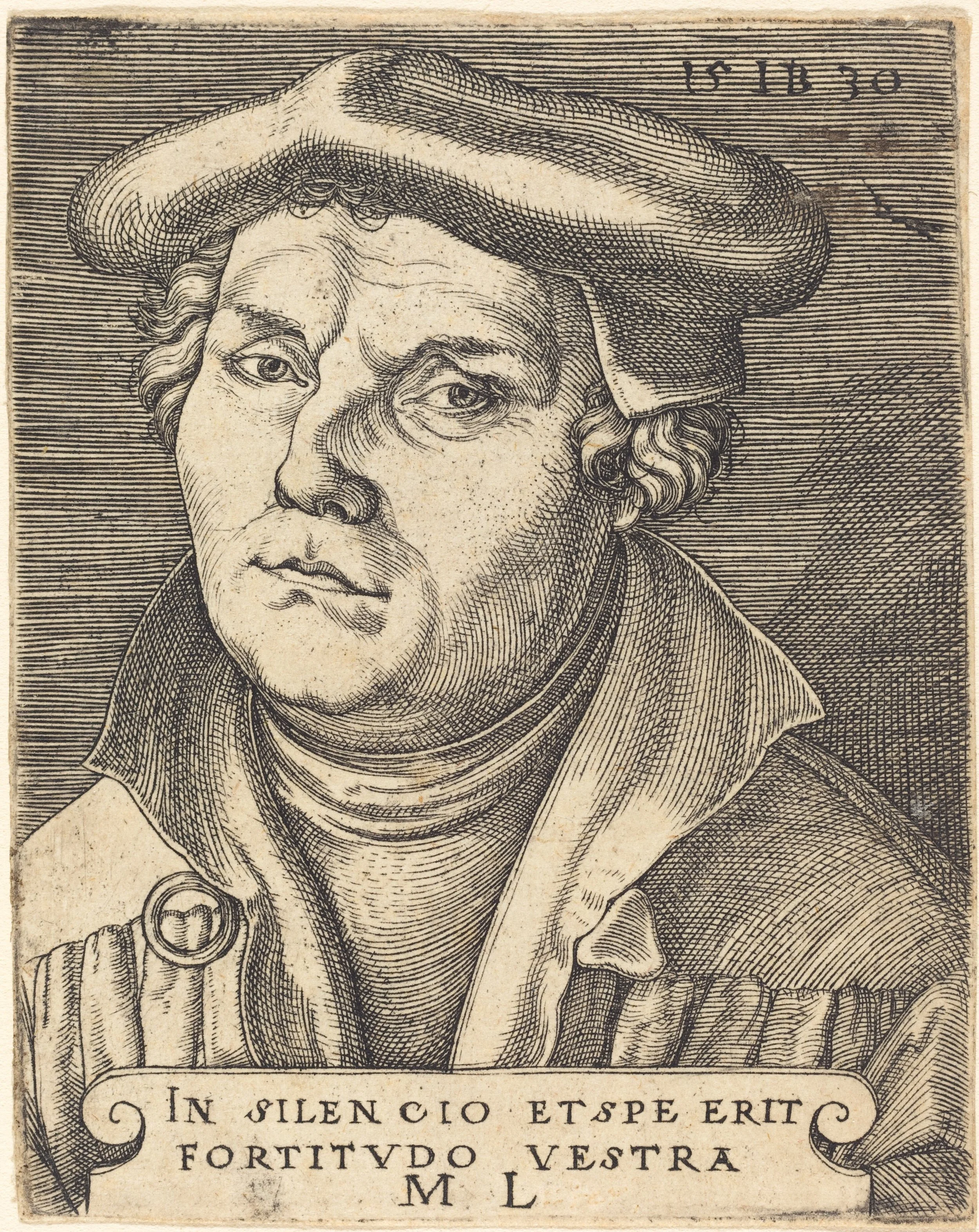

When I discovered the Reformation in college, it made becoming a historian irresistible. Aside from course textbooks, the first great history book I read was by the late Roland Bainton. It was his biography of Martin Luther, Here I Stand, published in 1950. What a magnificent introduction to historical literature that was! Bainton’s prose was unlike any history book I read up until that time. One reviewer said Bainton had the “ability to balance accuracy with storytelling, making complex theological worlds vivid for general readers while retaining academic integrity.”

Only later did I understand why I breezed through Bainton’s book, not once, but three times. I sensed for the first time that genuine history was a literary project, not a list of facts, causes and effects. Bainton could have been a successful novelist if he had chosen to write fiction.

Each Advent in preparation for Christmas, I read another of Bainton’s published works, Martin Luther’s Christmas. The book includes an introduction by Bainton. It comprises selections from the many sermons Luther preached on the Christmas story. This time, I gathered my zettels, or expanded notes, on Bainton’s insights from the book. I combined them with an actual Christmas sermon by Luther on Luke 2. I was working on a small project for another podcast episode and a blog article that compares Luther’s and John Calvin’s views on Christmas. That is coming up, but I wanted to give Luther his own treatment because he has more of a “heart” for Christmas. (Does Calvin have a head for it?) Calvin is a steady, assuring influence, but Luther is more relatable. I’m not a beer drinker, but if I were, I would want Luther as my drinking buddy! I will say more about these two pillars of the Protestant movement later.

Are you looking for the true meaning of Christmas tonight? Have you bowed your head in despair because its promise is adrift in a sea of naturalism, materialism, and hatred? I know a mentor from early modern history who can help us find it. It is the relatable Luther. The same lovable fellow who called his enemies animal and excrement names. I mean no sarcasm here. My virtual drinking buddy loved Christmas and shared his heart to help us grasp why.

I am saying, if you want to understand Martin Luther’s heart, don’t begin with his polemics; begin with his Christmas. Few passages in the Bible brought Luther nearer to tears than the Nativity story. In fact, when he preached on Luke 2:1-14, you can almost hear him stepping into the stable and gasping at what he sees.

For Luther, Christmas is an invasion, a divine descent so deep and so tender that no words can express it. The eternal God enters the world not in a shimmering palace but in the straw of a borrowed stall.¹

Luther begins by shaking us awake: Christ became our human as bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh. “For you,” Luther says again and again. “For you He is born.”

But Luther loves every detail of the story. He imagines Mary: a poor, unknown girl from Nazareth, trudging southward in winter. She might be riding a donkey. The text does not specify. But she was walking, exhausted and unnoticed.²

He imagines Joseph with no carpenter’s bench nearby, no family home to open, only an innkeeper’s shrug. He imagines their arrival in Bethlehem. The charming “little town” of song. Its out-of-town guests never think to give up a room to a woman in labor.³ Luther says the world is too busy to recognize its Savior.

And then there is the birth. No attendants. No warming fire. No midwife to help. Here is a young mother kneeling on the cold floor of a stable. She bends in the dark, wrapping her infant in whatever cloth she could spare.⁴

The Creator of the universe, the One who shaped Adam from the dust, now lies in a manger where animals feed. “Do you see,” Luther asks, “how God turns the world upside down?” He makes the high low; he lifts the low high. He exposes human wisdom as foolishness, human pride as blindness.

Bethlehem slept through the greatest moment in its history. It expected God in palaces rather than in poverty.⁵Yet Luther is no mere sentimentalist. He sees in the manger the first public declaration of Christ’s mission. Christ submitted to Caesar’s census even while in His mother’s womb. He shows that he has come not to overthrow human authority but to enter into human obedience. He endures poverty. It foreshadows Jesus’ lifelong humiliation that will culminate at the cross.⁶

But for Luther, the deepest miracle of Christmas is not that Christ humbled Himself. It is that He took up our shame to give us His glory. In a remarkable passage, Luther tells his hearers to imagine themselves in Mary’s place. “Make this birth your own,” he says. “Take the Child as if He were born from your own flesh.” For if Christ has taken your humanity, then His innocence becomes your innocence. His pure birth cleanses your impure one.⁷ Luther is particularly moved by the shepherds. They are living proof that the gospel belongs first to the humble and the low. They had no learning, no reputation, no theological sophistication. They heeded the angel’s instructions and went.⁸

And when they arrived, what did they find? Not what any reasonable person would expect. A Savior wrapped in rags instead of silk. The King of kings lying in straw and not eider-down pillows. The sign of God’s redemption, Luther says, is always humble, hidden, wrapped in the ordinary.

And here is one of Luther’s boldest insights: Do you claim you would have welcomed Christ that night in Bethlehem? Then you can show it now by welcoming Him in the person of your neighbor. The manger was a test of the world’s compassion, and the world failed. So every needy person we meet becomes, in Luther’s imagination, another Bethlehem. The presence of a stranger is another chance to receive Christ where we do not expect Him.⁹

Finally, Luther returns to the angels’ song. They say, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace.” He hears in that song the whole Gospel in miniature.

Glory to God, because salvation is His work alone.

Peace on earth, because Christ reconciles sinners to God the Father.

Goodwill toward those He has chosen, because God comes not in wrath but in mercy.¹⁰

For Luther, Christmas is a transformation. The Child in the manger is the God who claims us, cleanses us, and calls us into a life of humble love. The Nativity is not the beginning of Christ’s story; it is the beginning of ours.

Luther’s words were influential. He was the channel through whom Scripture, in the common tongue, changed the course of history. Luther gave Christmas back to people without decorations, song, or liquid cheer. Luther invited us to stand with the shepherds, bend low beside the manger, and consider. Mindful of a shattering truth rather than a quaint scene or a seasonal decoration. The Maker of all things has made Himself small, that He might make us sons and daughters of God.¹¹

Bainton, Roland H. Martin Luther’s Christmas Book. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1948.

Luther, Martin. “Sermons of Martin Luther, vol. 1.” John Nicholas Lenker, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House (1983).

Footnotes

¹ Roland H. Bainton, Martin Luther’s Christmas Book (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1948), introduction and commentary on Luther’s stripping away of medieval Nativity embellishment.

² Bainton, Martin Luther’s Christmas Book, on Luther’s humanizing portrayal of Mary’s poverty and journey.

³ Ibid., Bainton’s note on Luther’s tendency to weave the Nativity into the familiar social world of German domestic life.

⁴ Ibid., discussion of Luther’s focus on the stark and earthy realism of the birth.

⁵ Ibid., on Luther’s theology of the divine hiddenness and the world’s blindness to grace.

⁶ Ibid., on Luther’s linkage of Bethlehem and Calvary—humiliation as a single movement.

⁷ Ibid., summary of Luther’s teaching that Christ’s “pure birth” heals humanity’s “impure birth.”

⁸ Ibid., on the shepherds as paradigms of humble faith.

⁹ Ibid., Bainton’s note on Luther’s ethical turn: modern hearers would have failed Bethlehem’s test.

¹⁰ Ibid., on Luther’s exegesis of the angels’ hymn as a tightly compressed gospel.

¹¹ Ibid., concluding reflections on Luther’s emotionally rich and doctrinally grounded Christmas preaching.