Fast Away the Old Year Passes: Life’s last words of Hemingway, Hand, and Hearst

A New Year’s Eve Essay

The end of a year has a way of making us think about endings.

We look back over the old year and rack our brains for a clean sentence that makes sense of it. We exert that same effort at the end of a life. In fact, one of our subjects for this episode spent his entire life searching for a single clean sentence. And yet it wasn’t easy to close the books on Ernest Hemingway.

The thirst for a simple sentence to sum up things in a neat way is understandable. But it is also dangerous because lives do not end the way stories end. They do not always hand us a moral. They do not arrange their final moments into a tidy conclusion. Most of us do not get to write our own ending.

Life magazine is a legend in the American publishing world. Pioneering photojournalism, Life chronicled some of the most turbulent years in human history. It was a weekly visitor to subscribers’ homes until it ceased regular publication in 1972. When my mother died, I discovered she had saved a few magazines. As I sorted through the items that would make up her estate, I noticed the small stack of Life magazines. I picked one up. Because its cover showed a crowd of West Germans at the Berlin Wall. But as I read, I noticed that the selection of articles focused on the recent deaths of two famous Americans. Then I noted a retrospective commemorating the tenth anniversary of another’s passing. I don’t know if the editors planned it, but the juxtaposition of those three articles was poignant. The August 25, 1961, issue presented three American lives to its readers. Each represented a different kind of power. Each left behind “last words” that resist our desire for closure.

Ernest Hemingway was one of the most influential American writers of the twentieth century. He was famous for novels and short stories characterized by spare prose and a flamboyant lifestyle. He was a Nobel laureate whose public toughness masked a deep private struggle. He shot himself to death in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961.

The most respected American judge never to sit on the Supreme Court, Learned Hand shaped modern federal jurisprudence. He championed civil liberties but was wary of judicial overreach. He spent his life defending restraint, humility, and democratic limits.

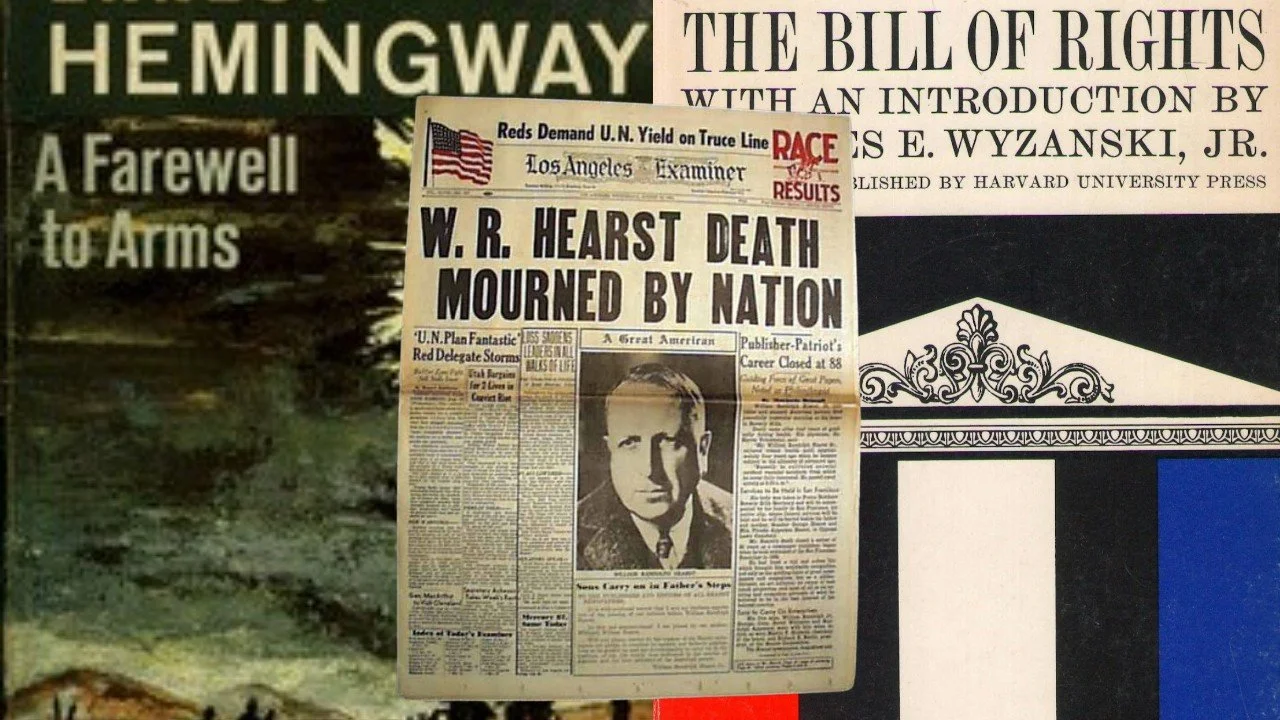

William Randolph Hearst was the most powerful newspaper publisher in American history. He came to prominence in the days of “yellow journalism.” His newspapers were a force capable of shaping national politics and public opinion. Having forever changed the power of the media to shape public policy, he died after a long physical decline.

At first glance, the contrast among them seems straightforward. The novelist, the judge, and the publisher; creativity, judgment, and influence; art, law, and power. But what makes their juxtaposition so revealing is that their deaths had similar features. None of their final words is what we would expect. What follows is not an attempt to explain these three endings, but to sit with them as Life magazine did. I begin with a letter written in surprising tenderness. Next, I will consider a life ended in humility, and conclude with a final confession of limits.

Hemingway’s “last words,” as Life revealed them, came less than two months after his suicide. They were not a statement to the world or a summation of a literary career. They were a handwritten letter to a nine-year-old boy. Frederic Gordon “Fritz” Saviers was the son of Hemingway’s physician. Young Fritz was in the hospital with a congenital heart condition.

The letter is ordinary. Hemingway wrote about the weather in Minnesota and about his surprise at the beauty of the Upper Mississippi. He continued about hunting pheasants and ducks in the fall. Ernest hoped that they would both be back in Idaho soon to joke about hospital experiences. He signed it as Fritz knew him: “Mister Papa.”

There is no farewell here. No self-interpretation. No hint that “Papa” meant these words to be final. The letter assumed a future.

We now know that assumption is a tragic mistake, yet it is what makes the letter so human. Hemingway did not write toward an ending. He wrote toward a living relationship.

The more we learn about the rest of the story, the deeper it goes. Fritz Saviers himself would die young, at fifteen, in 1967. Yet his life was not one of withdrawal from the limelight. He was a champion schoolboy skier, vigorous and competitive to the end. Today, at the foot of Hemingway’s grave in Ketchum, facing it, lies Fritz’s own grave.

That physical closeness does not complete a story. It refuses to.

Hemingway’s last words remind us how life continues in a relationship even as history prepares to close the book. But Learned Hand’s final season asks a different question. How does a judge’s life, one devoted to judgment, end when final judgment comes?

The Life article on Learned Hand offers no dramatic last utterance. Instead, it gives us a posture.

Hand was old, weak in body, trembling, and the voice quavering. Yet his mind remained alert and serious. He reflected on tyranny, ambition, and human frailty. As was his wont, he resisted straightforward explanations and moral slogans. He distrusted what he called “pretty phrases.” He worried about rationalization. He refused certainty.

Hand did not turn his imminent death into a litany of regrets. He did not claim wisdom in retrospect. He did not sanctify his career. He sprinkled his final words across remembered conversations. His words were consistent with the discipline that marked his life. He prized humility above power, demonstrating restraint in the face of moral temptation.

Where Hemingway’s last words preserved tenderness, Hand’s preserved doubt, and his ending teaches us the discipline of restraint. Hearst’s final years confront us with the harsh truth of what happens when power outlives the body that once commanded it.

William Randolph Hearst lived as a man who sought to shape the reality he chose to report. His newspapers labored to form public opinion rather than record it. For decades, he wielded influence on a national scale.

Life magazine’s retrospective recounted his early years of building a publishing empire. Yet the portrait of Hearst’s final years is a study in diminishing control.

Frail and isolated, he still tried to run his empire. He issued instructions at odd hours about ideological crusades. He worried over foreign affairs and editorial minutiae. But the machinery he had built no longer obeyed him as it once had. Editors pressed harder than he wished. The family and the executives are prepared for succession. Authority slipped, even as the habit of command remained.

Then came the moment that functions as Hearst’s most revealing “last word.” Hearst summoned an editor in anger about a story he believed his staff had ignored. The editor presented Hearst with the published article, written exactly as ordered. The old publisher stared at it, then spoke in a failing voice:

“Mr. Woolard, forgive me. I’m sorry. You know I’m an old man, sick, and I don’t notice things as well as I used to.”

It is the unexpected: an apology.

Hearst died shortly thereafter. His mistress of thirty-five years, Marion Davies, slept through his passing. Doctors sedated her amid family tension. Hearst’s funeral was grand and theatrical, befitting a titan of media and politics. Yet former actress Marion resisted the spectacle, saying, “There’s no need for dramatics.” Hearst died as all men do.

Taken together, these three lives form a revealing New Year meditation. Hemingway, the maker of stories, leaves words that do not foreshadow an ending to his story. Hand, the maker of judgments, leaves life refusing to pronounce judgment. Hearst, the maker of headlines, leaves an apology that admits to diminished power.

None of these great men mastered the meaning of his own death. Could that be the lesson worth carrying into a new year?

Celebrity tempts us to reduce lives to symbols and endings to verdicts. But these three stories resist that impulse. They remind us that we live life forward, not backward. Endings interrupt more than they explain. “Last words” are often not conclusions at all, but fragments of life still in motion.

Hemingway signs, Papa. Hand doubts. Hearst asks forgiveness. Life is not a thing we master. We live it.

I confess to enjoying reading this issue of Life magazine, but these three “last words” left me sad. It is because, while their lives were still in motion, these men finally came to view them as past. You are about to hear what you could construe to be my last words for 2025. I have not mastered life; I don’t expect to; and I am thankful for a second chance, symbolized by the end of an old year and the beginning of a new. I have no idea whether I will make it to the new year. Still, even at seventy, I know real life is only beginning.

As the Christmas carol says, “Fast away the old year passes.” But the next verse says, “Hail the New, ye lads and lasses!”

I say farewell to the old year with part of an old Irish blessing:

Always remember to forget

The troubles that passed away.

But never forget to remember

The blessings that come each day.

And those are you, “ye lads and lasses!” Happy New Year!